How To Become A Cult Leader, Part One

The story of how Steve Jobs turned users into believers and belief into identity.

“Totalism is the disposition to view life through an all-or-nothing lens—a mode of thought where nuance is not simply ignored, but made impossible.”

— Robert Jay Lifton, Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism

There is no shortage of resources for those who want to influence. Dale Carnegie taught us how to win friends. Sun Tzu taught us how to wage psychological war. Robert Greene promises power in 48 steps. But in the contemporary attention economy, these tactics are no longer enough.

Today’s increasingly dominant archetype is not the strategist or the salesman. It’s the cult leader. Not as you know them: they are not found in white robes hiding off in desert communes. They are the algorithmically optimized influencer, the venture-backed founder, the managerial evangelist proselytizing on LinkedIn.

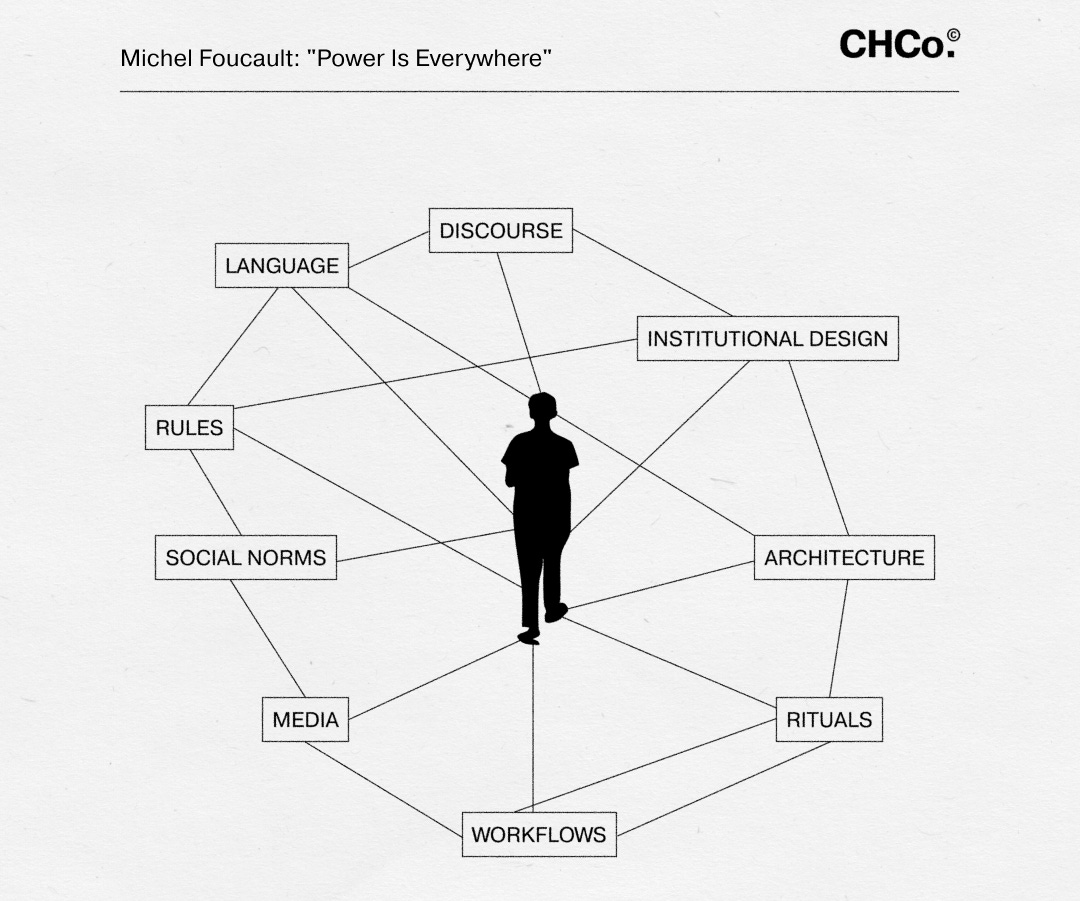

This ever-present architecture of power does not operate on direct force, but in dispersion and diffusion. Michel Foucault identified that such “power is everywhere… because it comes from everywhere.” It doesn’t reside in a single source but emerges from a “complex strategic situation” produced by discourse, institutional design, and everyday rituals of consumption and connection.

This control radiates outward. As Robert Jay Lifton notes in his study of ideological totalism control radiates outward, using vectors such as aesthetics, language, and ideological recursion (channels that humans are wired to follow) and redefine reality to such an extent that resistance becomes unintelligible.

For a deeper reading, we can look to Jacques Lacan’s frameworks of language’s role in the formation of subjectivity. The subject is not sovereign, that is, not the supreme arbiter of their own reality. They are formed within the Symbolic Order, a structure of meaning that precedes and conditions selfhood. What appears to be persuasion is actually a process of structural reconstitution. The subject is formed through language it never chose.

When that language is set by a brand or belief system, what we call “affiliation” is really ontological absorption.

This series is a field manual for how engineered devotion is constructed. It was drawn and developed from the clinical literature of cult psychology, the tactics of political propaganda, the architectures of algorithmic persuasion, and the aesthetics of brand mythology.

As follows are the six structural pillars of cult control. Each one maps onto the mechanics of identity construction, emotional dependency, semantic control, and behavioral feedback.

Identity

Devotion

Ritual

Symbolism

Language

Obsession

Each of these is an independent unit of influence and a mutually reinforcing subsystem. This series dissects them one by one, beginning with identity: the core structure through which all other pillars gain operational legitimacy.

Identity as Infrastructure

Objective: Disrupt and replace the subject's interpretive framework through symbolic saturation, ritualized behavior, and ontological conditioning.

This is Part 1 of a six-part series on engineered belief. Next, we’ll examine how devotion is built through repetition, emotional leverage, and escalating commitment.

How Steve Jobs Restructured Identity:

Narrative Control: Transformed personal charisma into a mythos that fused his identity with Apple’s.

Strategic Opposition: Cast Apple against IBM to create disidentification and reframe computing as self-expression.

Emotional Volatility: Manipulated teams through alternating praise and punishment to foster psychological dependency.

Design as Doctrine: Used design psychology (e.g., rounded corners = safety) to embed emotional trust in physical objects.

Identity Alignment: Positioned users as protagonists in a moral narrative.

Milieu Control: Controlled the entire user environment to eliminate ideological dissonance.

Ontological Fusion: Collapsed the boundary between product and self; users became the brand.

Semantic Closure: Created a closed-loop system of meaning.

Seductive Power: Made belief feel like common sense.

Steve Jobs did not read How to Win Friends and Influence People. He read Alan Kay, the computing visionary behind the graphical user interface. He read Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalogue. He read Marshall McLuhan’s theory of media and understood what McLuhan meant when he wrote “the medium is the message.” Jobs set out to ensure that the medium, the message, and the self would become indistinguishable within Apple’s ecosystem. He reframed the entire computing industry around personhood.

His vision centered on personal agency. While others touted processing power or efficiency, Jobs offered an existential benefit. Here was a computer, a technology, designed as extension of the self.

“Jobs could seduce and charm people at will, and he liked to do so,” wrote Walter Isaacson. “People such as Amelio and Sculley allowed themselves to believe that because Jobs was charming them, it meant that he liked and respected them. It was an impression that he sometimes fostered by dishing out insincere flattery to those hungry for it.” *

Seduction and charm can be employed as a form of conditioning. But charm alone doesn’t produce devotion. To sustain influence at scale, the leader must craft something more enduring: a mythology.

Charisma must calcify into narrative. Jobs, like many cult leaders, turned his reputation into the infrastructure for his control.

In The 48 Laws of Power, Robert Greene warns: "So much depends on reputation, guard it with your life." All good cult leaders know this to be true. L. Ron Hubbard famously constructed an elaborate personal mythology, falsely claiming heroic naval exploits and academic credentials to bolster his authority. Shoko Asahara, the founder of Aum Shinrikyo, positioned himself as both a divine entity and a scientific visionary, blending esoteric Buddhism with pseudo-scientific jargon to secure elite adherence. Even Charles Manson styled himself as a prophet, reworking Christian apocalypse narratives to justify his commands.

Jobs curated his own cosmology. The myth of the dropout genius in the garage. The guru in the Issey Miyake black turtleneck. The minimalist who understood the soul of the machine. He was a symbol. And he ensured that Apple’s identity could never be separated from his own.

Identity disruption begins with a break from the old system. For Jobs, this was institutional computing. In the 1970s, computers were mainframe-bound, impersonal, bureaucratic, and optimized for enterprise. Apple’s foundational thesis was rupture: the computer not as infrastructure, but as a mirror. The personal computer as self-expression device.

This seems self-evident today, but this was a massive dissent from how these machines had previously been marketed. Most computing was about efficiency. The conversation between creativity and computation hadn’t been culturally forged. There was a divide: creatives and technicians, art and logic. Jobs and his head full of acid aimed to collapse the binary. To offer aspiration to the technicians (“You too can be an artist”) and offer creative amplification to the rebels (“Here’s the future. Build it.”)

In 1976, Jobs and Steve Wozniak launched the Apple I: a bare motherboard priced at $666.66, a number Wozniak liked for its repeating elegance. It wasn’t built for corporations. It wasn’t designed to centralize power. It was made for individuals, hackers, hobbyists, and outsiders.

By the time Andy Hertzfeld joined the Macintosh team in 1979, Apple had grown from countercultural experiment to ideological movement. Hertzfeld described Jobs as operating within a “reality distortion field”, a psychic forcefield of charisma, certainty, and rhetorical velocity that could bend timelines, people, and facts to his will. Even employees who knew they were being manipulated often found themselves believing anyway. “Reality,” one said, “was malleable in his presence.” *

Hertzfeld described it as “a confounding mélange of a charismatic rhetorical style, an indomitable will, and an eagerness to bend any fact to fit the purpose at hand.” If one line of argument failed, Jobs would simply shift position, often adopting your viewpoint as if it had always been his.

Jobs engineered a dual system of control: emotional manipulation on the inside, aesthetic seduction on the outside. Internally, he cycled through praise and punishment, forging what psychologists call disorganized attachment. One day you were a genius. The next, a failure. The result was dependency. Devotion was maintained through volatility. Employees didn’t just want to build great products. They wanted to be seen as great by Steve.

As one Business Insider anecdote reveals, “He’d work a room, alternate between seduction and cruelty. One day, he’d praise your idea. The next, he’d pitch it back to you as his own.” By blurring affirmation and appropriation, he destabilized ego and reinforced dependence. The result was a sustained state of psychic vigilance: to stay close to Jobs, one had to continuously recalibrate the self.

Externally, he deployed a different toolset. Where cults use love bombing to overwhelm the initiate with affirmation, Jobs used beauty. The rounded corners. The glassy iconography. The minimal packaging. In design psychology, rounded shapes are perceived as safer, more approachable, and more human. They signal softness, not threat. As explored in the Bouba-Kiki effect, people instinctively associate soft, rounded sounds with curved shapes and sharp, jarring sounds with jagged ones. Sharp edges connote danger; curves invite touch. Jobs built talismans that disarmed skepticism through tactility. To own a Mac wasn’t to own a machine but to own a piece of art.

The power of the system didn’t end at the object or the office. Influence, to endure, must be refracted, carried not just by the leader, but by the believer. What Jobs constructed internally through manipulation and externally through design became self-reinforcing once reflected back by those willing to be shaped.

Charisma, as Max Weber defined it, is a form of legitimate authority grounded in the belief that the leader possesses “supernatural, superhuman, or at least specifically exceptional powers.” That belief, he wrote, must be “recognized by those to whom he feels he has been sent. If they recognize him, he is their master.”*

Consumers were cast as protagonists in a larger moral narrative. Rebellion was the brand promise. Transformation, the reward.

Apple was anointing misfits, creatives, and rebels with aspirational character. The ad didn’t say “join us,” it said “you’ve always been one of us.” It reframed ownership as affirmation: not “I use Apple because I’m different,” but “I’m different; therefore, I use Apple.”

The rebirth narrative followed suit. IBM symbolized mechanical logic, institutional scale, and bureaucratic conformity. Apple, by contrast, embodied intuition, creativity, and the sovereignty of the individual. Platform choice became a form of philosophical alignment. Switching systems signaled a departure from submission and a movement toward self-authorship.

That transition had to be supported not just by belief, but by structure.

Lifton’s concept of milieu control describes how control over one’s perceptual environment can shape reality itself. Jobs operationalized this. Every touchpoint, device, software, store, packaging, onboarding was designed to collapse cognitive dissonance. The aesthetic and functional ecosystem left little room for ideological escape. To engage with Apple was to inhabit a worldview, reinforced at every sensory and symbolic level.

This structural enclosure created brand loyalty to the point of ontological dependency. The more immersive the design, the less separable the user became. Identity fusion followed. Apple no longer represented a choice. It became the natural habitat of the creative self. People didn’t describe what they used. They described what they were: “I’m a Mac person.”

In this way, power was never imposed. It was enacted through seduction. As Byung-Chul Han writes, “Power today does not repress. It seduces.”

This is the architecture of cultic infrastructure: the systematic reshaping of identity through repetition, enclosure, and implied transcendence. Jobs didn’t need to demand belief. He built a world where belief became the only coherent option for his followers, his employees, and eventually, his users.