The Algorithm as Ritual

Meta, Thought Reform, and the Architecture of Perception

From the songs we play to the headlines we read, algorithms have become the invisible hand guiding our (online) lives. The convenience of curation, that quiet assurance that after we like, share, or subscribe, something similar will appear, has been normalized to the point of invisibility. Yet this infrastructure, in its current manifestation, is barely a decade old. What began as a crude mechanism for matching “stereotyped” user preferences has evolved into a massive machine of influence, one that, in the hands of Meta, functions less like a mirror and more like a totalizing environment designed for behavioral shaping.

In the era of AI-driven generative recommenders (GRs), Meta’s current algorithms operate as a form of milieu control, enclosing users within a curated reality while also obscuring the mechanisms of influence. Robert Jay Lifton defines milieu control as “the control of human communication, not only the individual’s communication with the outside but also… with himself” (Losing Reality, 2019). In physical cults, this meant sealing members off from dissenting voices; in the algorithmic era, Meta achieves the same effect through a feed that becomes the user’s primary environment for perception and thought. Competing narratives are quietly downranked, filtered, or never shown.

“The most basic feature of the thought reform environment, the psychological current upon which all else depends, is the control of human communication. Such control not only inhibits the individual’s capacity to test reality independently; it also creates a closed system of logic and authority.”

Robert Jay Lifton, Losing Reality, 2019

♡*Grundy to Generative Recommenders *♡

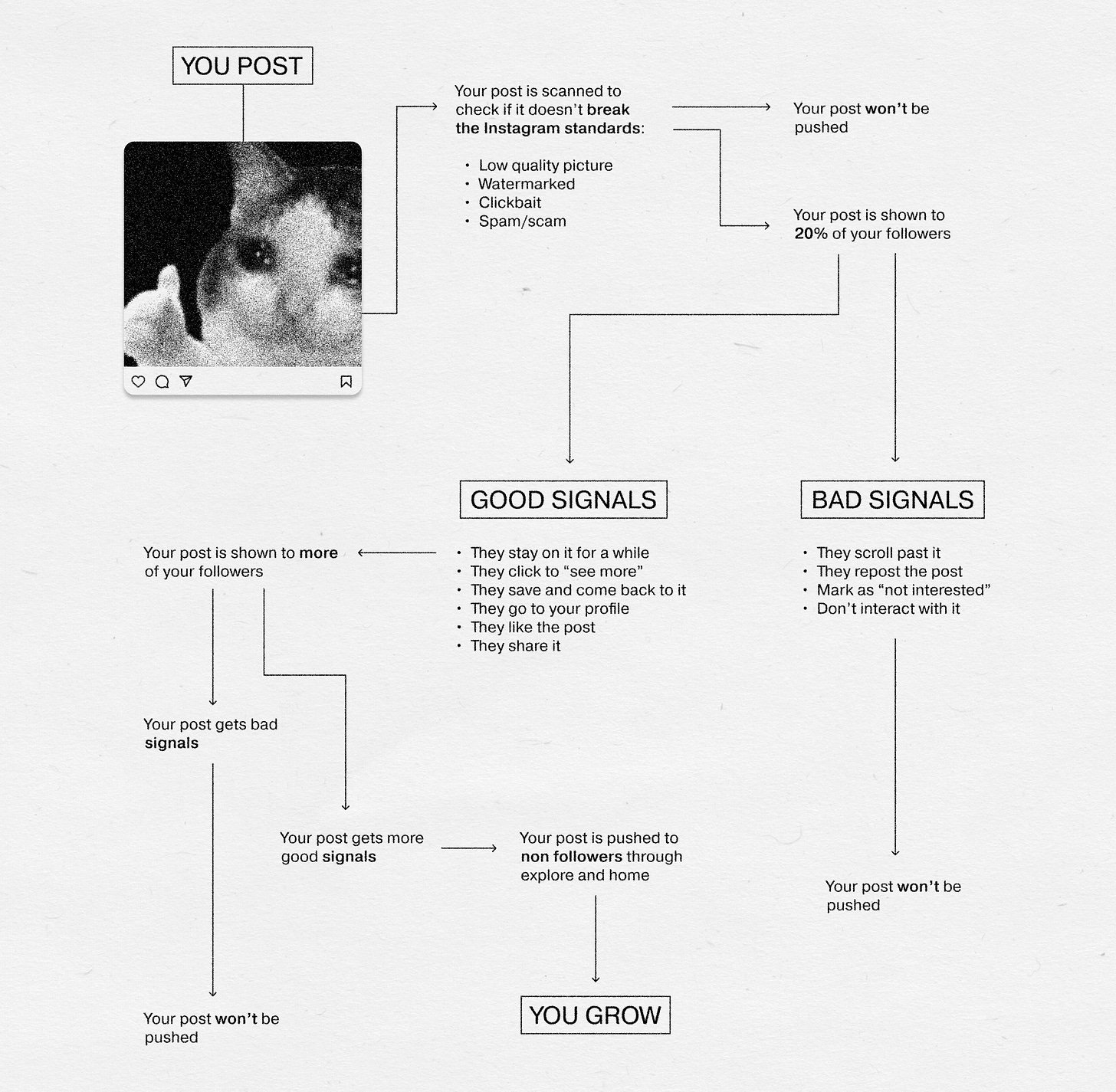

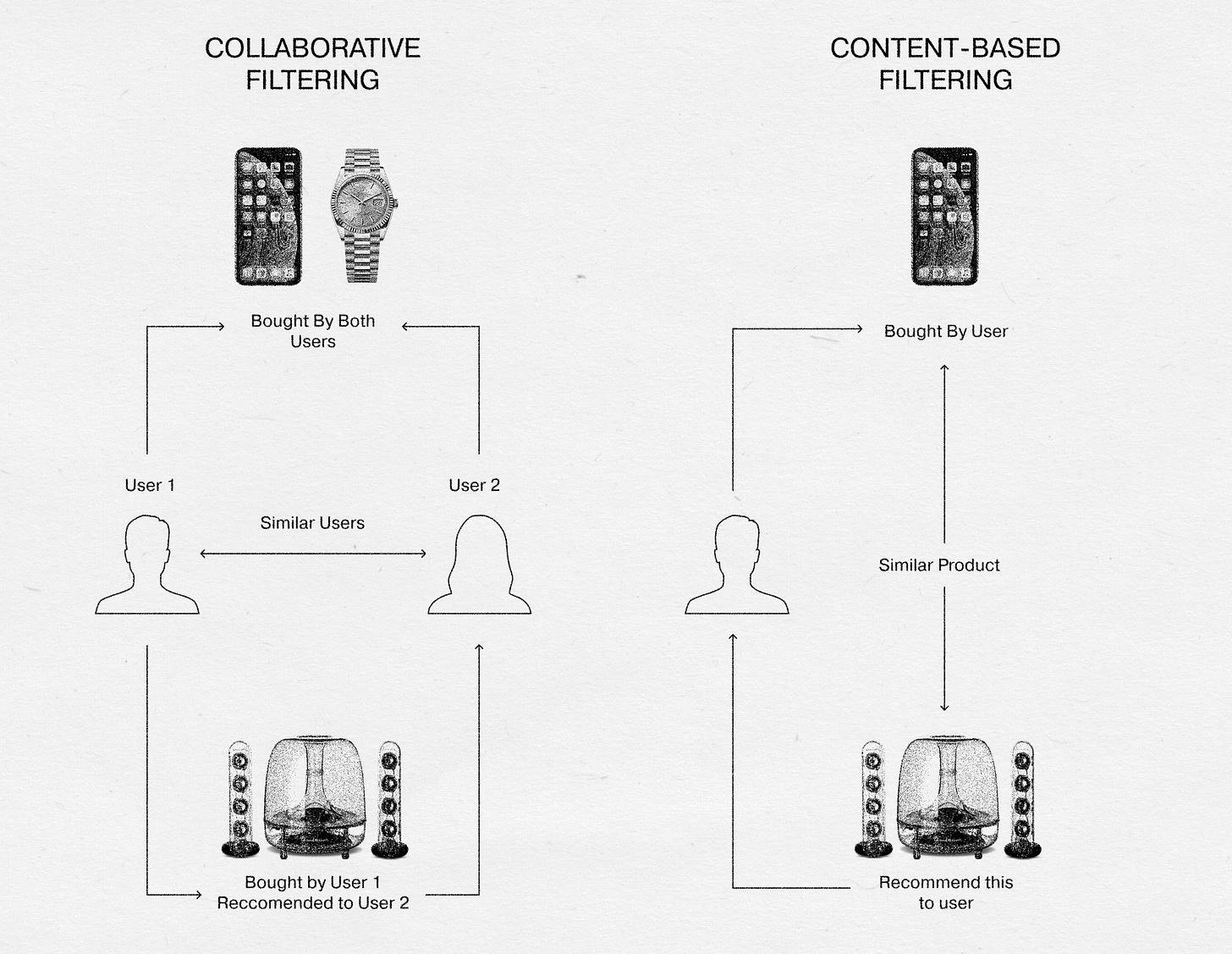

Elaine Rich’s 1979 Grundy system was rule-based and explicit: the system asked questions, sorted users into stereotypes, and recommended accordingly. Collaborative filtering in the 1980s and 1990s gave way to probabilistic matching; if two users liked similar things in the past, it was probable they would like similar things in the future. In parallel, content-based filtering compared the attributes of items themselves, matching the descriptive features of past favorites to new options, independent of other users’ behavior. Early adopters like Firefly, Pandora, and Amazon proved the commercial value, but the Netflix Prize turned recommender systems into an industry-wide competition.

In 2006, Netflix offered $1,000,000 to any team that could improve its algorithm by 10% using a dataset of more than 100 million movie ratings. On September 21, 2009, BellKor’s Pragmatic Chaos claimed the win; a planned follow-up in 2010 was canceled after researchers showed the dataset had been leaked.

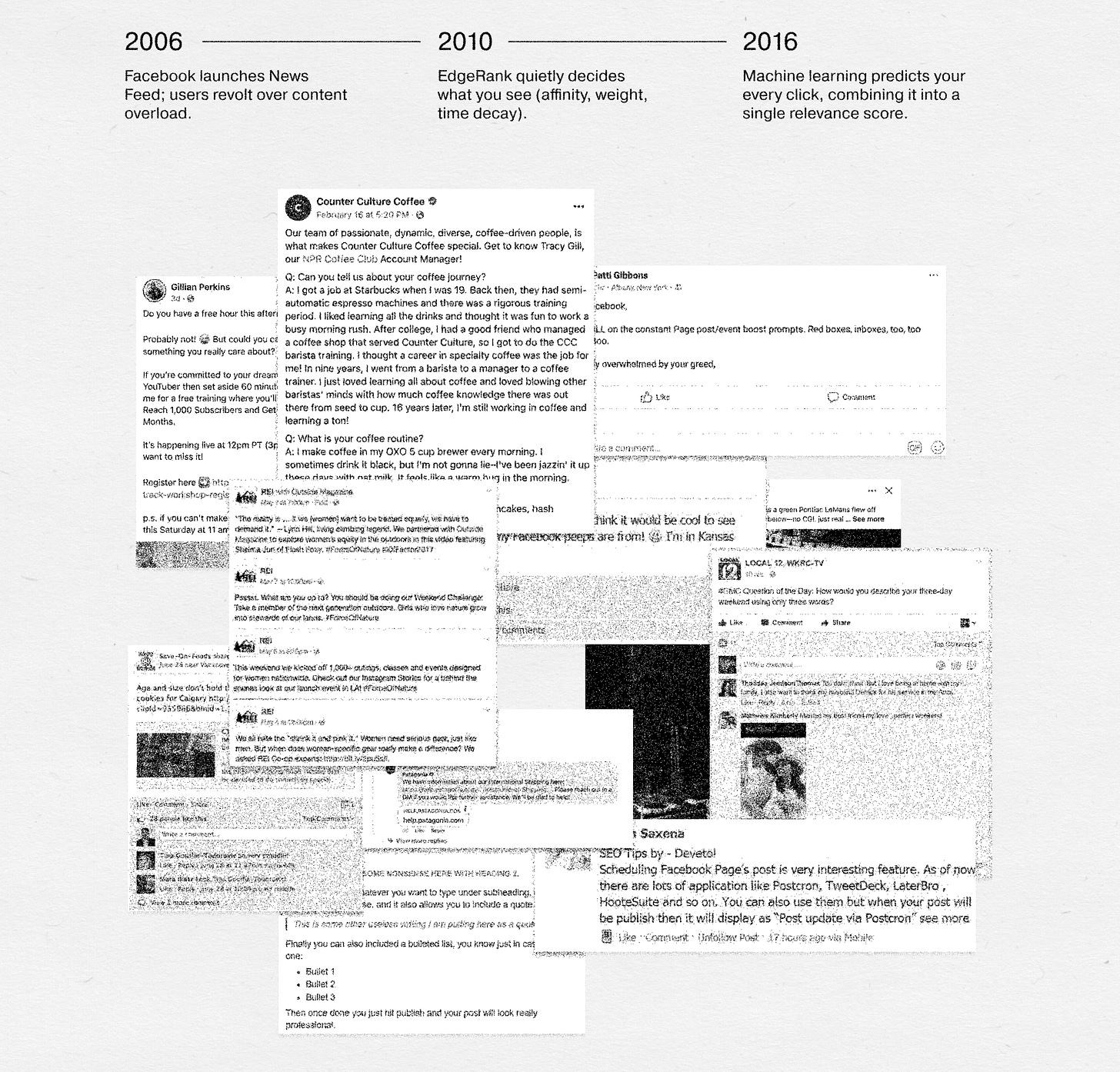

That same year, Facebook launched its chronological News Feed, which was met with widespread criticism; users felt overwhelmed by the volume of posts and struggled to find relevant content. By 2010, Facebook introduced EdgeRank, a proprietary content ranking formula based on three factors: affinity, weight, and time decay. EdgeRank was eventually replaced by machine learning systems. By 2016, Meta entered the “Relevance + Prediction” era, training separate models to forecast specific engagement types (comments, shares, hides) and combining these into a single overall relevance score.

Beginning in 2020, Meta shifted its ranking systems into what it calls AI-driven generative recommenders (GRs). Large-scale transformer models, akin to those behind GPT, interpret user behavior as a predictive language, forecasting not only what a person will click, but also how long they will linger, how they will react, and whether that interaction will lead to more time on the platform. Some of these models reach 1.5 trillion parameters and, in live testing, have produced engagement increases well into the double digits, surpassing the 10% improvement that once defined a breakthrough in recommendation technology. The objective is not to “show the best content” but to optimize for engagement, satisfaction, safety, retention, and advertiser outcomes.

“When you enter a filter bubble, you don’t choose what’s in it—and you don’t particularly know what’s left out.”

— Eli Pariser, The Filter Bubble

⋆☽ The Ritual of Scrolling ☽⋆

“Variable reinforcement schedules—the same behavioral design that makes slot machines so addictive—are built into social media feeds. Because the rewards are unpredictable, our brains release more dopamine than if they were guaranteed. This mechanism is one reason heavy social media use has been linked to patterns of compulsive behavior similar to a gambling disorder.”

— Sinan Aral, The Hype Machine (2020)

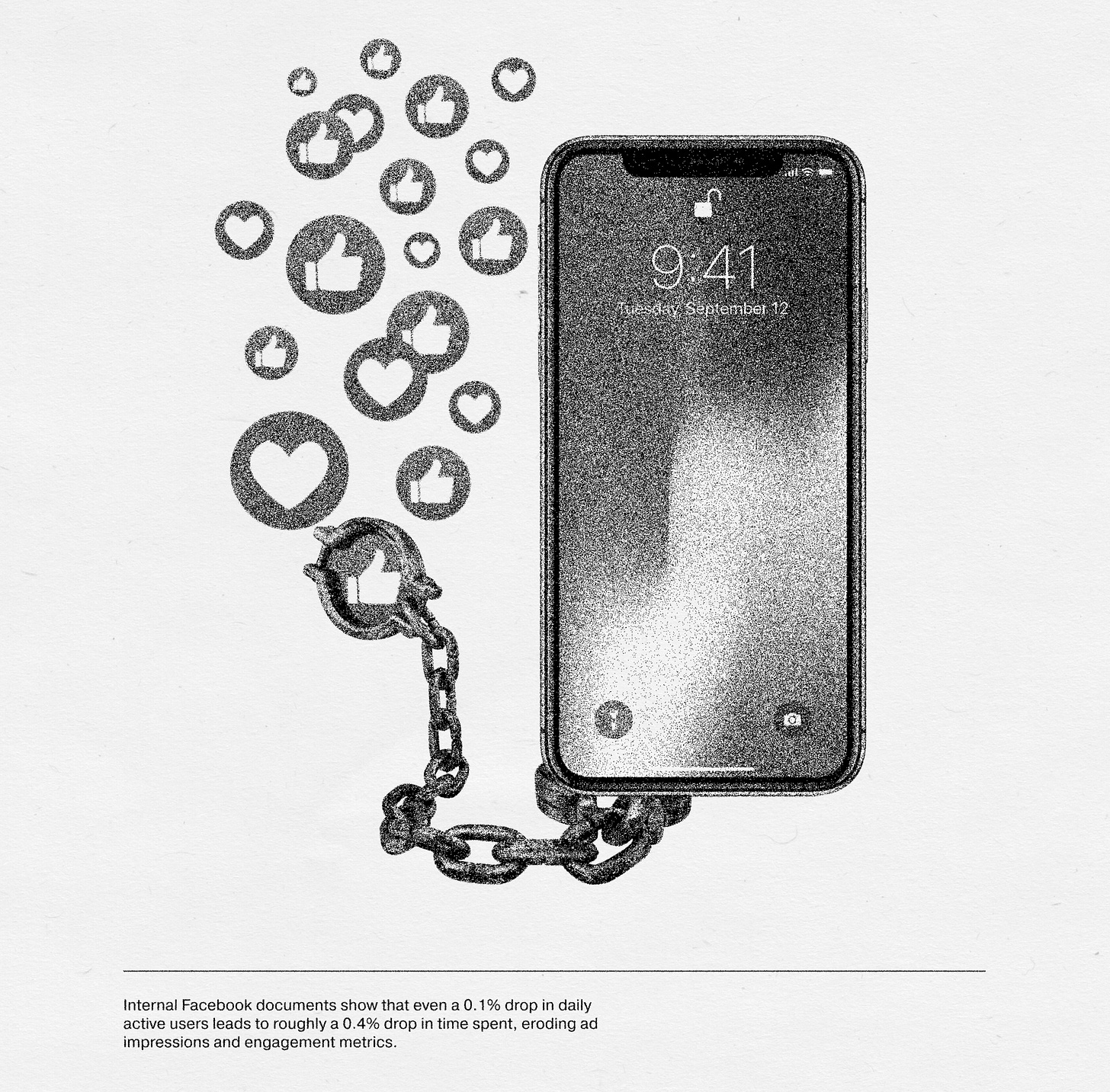

When Facebook tested infinite scroll on mobile, the time users spent on the platform increased by 20 to 40 percent, a boost consistent with the gains casinos see when they remove clocks and natural stopping cues. By eliminating natural stopping points, the interface turns each swipe into a conditioned action, reinforced by unpredictable rewards (novelty, outrage, social validation). Alexandra Stein’s research on coercive control notes that ritualized behaviors serve to reinforce attachment to the controlling entity. In Meta’s case, the ritual is the scroll, and the attachment is to the platform itself.

This ritual is both participatory and predatory: every scroll generates new data, which refines the model, which produces more finely tuned content, which prompts more scrolling. The loop is self-reinforcing and potentially endless, a digital equivalent of what Steven Hassan calls a “phobia indoctrination” environment, where the cost of disengaging feels higher than the cost of staying in. Globally, the average Facebook user now spends roughly 33 minutes per day on the platform; multiplied across Meta’s 3 billion monthly active users, this amounts to over 1.6 billion collective hours daily, time directly convertible into advertising revenue that exceeded $134 billion in 2023.

༶⋆˙⊹ Media Shaping ⊹˙⋆༶

Meta’s role as a global news distributor has fundamentally reshaped media production. Newsrooms now tailor headlines, imagery, and publishing cadence to align with the algorithm’s engagement preferences, preferences that research shows often reward emotionally charged, identity-confirming, or outrage-inducing content. A 2018 MIT Media Lab study found that false news stories on Twitter were 70% more likely to be retweeted than true ones, a dynamic that Facebook’s engagement-driven ranking similarly accelerates.

During elections, these algorithmic biases can have measurable effects. A 2021 NYU Cybersecurity for Democracy report analyzing Facebook engagement during the U.S. election cycle found that right-leaning outlets consistently earned higher interaction rates than left-leaning or centrist ones, regardless of factual accuracy. Internal Facebook documents leaked by Frances Haugen in 2021 revealed that ranking changes introduced in 2018 increased the spread of misinformation by up to 32%.

Linguistic determinism, the theory that the language you speak determines what you are capable of thinking, adds another layer. If moderation policies downrank or remove certain words, framings, or concepts, those ideas become less visible, less thinkable. As Frank Pasquale warns in The Black Box Society, “control over search and ranking is control over knowledge itself.” In electoral contexts, this narrowing of expression constricts the range of politically imaginable futures.

✦Breaking the Enclosure ✦

Escaping an AI-driven, engagement-optimized feed requires more than simply deleting an app or adjusting a few settings. It demands a dual approach: dismantling the infrastructure of control that platforms have built, and retraining the internal habits that keep users dependent on it. As Robert Jay Lifton (Thought Reform and the Psychology of Totalism), Alexandra Stein (Terror, Love and Brainwashing), Steven Hassan (Combating Cult Mind Control), Eli Pariser (The Filter Bubble), Frank Pasquale (The Black Box Society), Sinan Aral (The Hype Machine), and Christopher Bail (Breaking the Social Media Prism) argue, both system-level reform and individual-level awareness are necessary.

The first action is to reclaim perceptual autonomy. Treat the feed as an engineered environment, not as an unbiased reflection of the world. Learn to identify manipulation patterns such as repetition, emotional intensification, and selective exposure, all of which Lifton and Stein describe as core to thought reform. Hassan emphasizes the value of naming these tactics to break their unconscious influence.

The second action is to diversify information inputs. Do not rely exclusively on platform-ranked feeds. Actively seek out independent publications, newsletters, and direct-source materials. Use tools that introduce unaligned or contradictory perspectives into your daily media intake, interrupting the closed-loop reality described by Pariser in The Filter Bubble.

The third action is to decentralize connection. Reduce dependence on social networks for a sense of belonging by creating or joining communities that exist outside corporate platforms. Stein notes that controlling social bonds is one of the strongest levers of coercive environments.

The fourth action is to enforce transparency. Support legislation and civic initiatives that require platforms to disclose ranking criteria and allow independent audits, as Pasquale calls for in The Black Box Society. Push for user control over personalization settings, and for clear, public explanations of moderation rules.

The fifth action is to redesign incentive structures. As Aral argues in The Hype Machine, when engagement metrics are the primary measure of success, platforms will inevitably favor outrage and compulsion. Advocate for regulatory and design changes that introduce friction points, such as confirmation prompts before sharing unverified content or slowing the spread of emotionally charged posts.

The sixth action is to rebuild cognitive sovereignty. Follow Bail’s suggestion in Breaking the Social Media Prism to treat attention as a scarce resource. Schedule deliberate times for online engagement rather than defaulting to constant exposure. Replace passive scrolling with intentional, limited consumption rituals that you set yourself, removing the algorithm’s control over the rhythm of your attention.

Freedom from algorithmic milieu control comes from dissolving the power imbalance between the platform and the user. Structural change is necessary to weaken the system’s influence, and personal change is necessary to prevent it from taking root again.

⋞⟡To Refuse the Ritual ⟡⋟

To abstain from the ritual of the algorithm is to step outside Zuckerberg’s engineered cadence, to sever the feedback loop where each gesture is tracked, predicted, and re-fed to you for maximum retention. Internal Facebook documents leaked by the British Parliament show that even a 0.1% drop in daily active users lead to roughly a 0.4% drop in time spent on the platform, eroding ad impressions and engagement metrics.

Without your participation, the system loses the continuous data stream that sustains its precision. Over time, as Frank Pasquale notes in The Black Box Society, the predictive accuracy of such systems degrades without constant behavioral input. Robert Jay Lifton’s terms, it is the re-opening of the milieu, the return of air to a room that had been sealed. In practical terms, this is freedom: your attention no longer fuels the machinery that defines what you see, how you think, and which futures you can imagine.

Written + researched by ☠︎︎ ⋆₊ ♱ Alyssa Bonanno ☠︎︎ ⋆₊ ♱, cult leader of Cult Holdings Co

Sources

Bibliography

Aral, Sinan. The Hype Machine. New York: Currency, 2020.

Bail, Christopher A. Breaking the Social Media Prism: How to Make Our Platforms Less Polarizing. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2021.

Hassan, Steven. Combating Cult Mind Control: The #1 Best-selling Guide to Protection, Rescue, and Recovery from Destructive Cults. Rochester, VT: Park Street Press, 1990.

Lifton, Robert Jay. Losing Reality: On Cults, Cultism, and the Mindset of Political and Religious Zealotry. New York: The New Press, 2019.

Pariser, Eli. The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You. New York: Penguin Press, 2011.

Pasquale, Frank. The Black Box Society: The Secret Algorithms That Control Money and Information. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015.

Stein, Alexandra. Terror, Love and Brainwashing: Attachment in Cults and Totalitarian Systems. London: Routledge, 2017.

Vosoughi, Soroush, Deb Roy, and Sinan Aral. "The spread of true and false news online." Science 359, no. 6380 (2018): 1146–1151. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/study-false-news-spreads-faster-truth

Zhang, Eric, and Jon Hsu. “Is This the ChatGPT Moment for Recommendation Systems?” Shaped. March 19, 2024. https://www.shaped.ai/blog/is-this-the-chatgpt-moment-for-recommendation-systems.

Chayka, Kyle. "The Age of Algorithmic Anxiety." The New Yorker, July 25, 2022. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/infinite-scroll/the-age-of-algorithmic-anxiety.

Meta Platforms, Inc. "Newsroom." Meta Newsroom. https://about.fb.com/news.

Meta Platforms, Inc. "Transparency Center." Meta Transparency Center. https://transparency.meta.com

What a thought inspiring article! The paragraph about allowing air into the room hit me the most. I turned off my IG notifications and just checked my screen time, it’s not even on there anymore. Substack is my most used platform now. I’ve added the books to my goodreads too! Thank you for such a powerful piece - I’m looking forward to more of your work.